My Boston Sojourn

Funny how things work out. When I first arrived in Boston from New York, my ambition was to work at the Boston Globe. Coming off of the relentless pace of consumer magazines, where I was involved in everything from photoshoots to press checks, the predictable schedule of a daily held a certain appeal, especially with a toddler at home. What’s more, I had always been a news junkie, devouring newspapers since I was a kid. Exhibit one: In my sophomore year in high school, each week in history class (which everyone except me hated), we were treated to copies of the Chicago Tribune or the Detroit Free Press, which I found fascinating, my window to the big city. My peers, meanwhile, simply gazed wearily out the window.

Prior to and after our exodus from Gotham City, I worked at Newsweek on the Election Issue and other specials extending into the spring of ’95, commuting via air shuttle, which were quick, convenient, and affordable back then. I landed my first Boston assignment with prim culinary master Christopher Kimball, editor and publisher of America’s Test Kitchen and Cook’s Illustrated magazine. Kimball scored rising star editor Anne Alexander to head his newly-acquired magazine Natural Health. My brief was to repackage the crunchy, niche publication into a mainstream title that appealed to a broader audience of health evangelists. After about a year, Kimball flipped it, pocketing millions in profit. Mission accomplished.

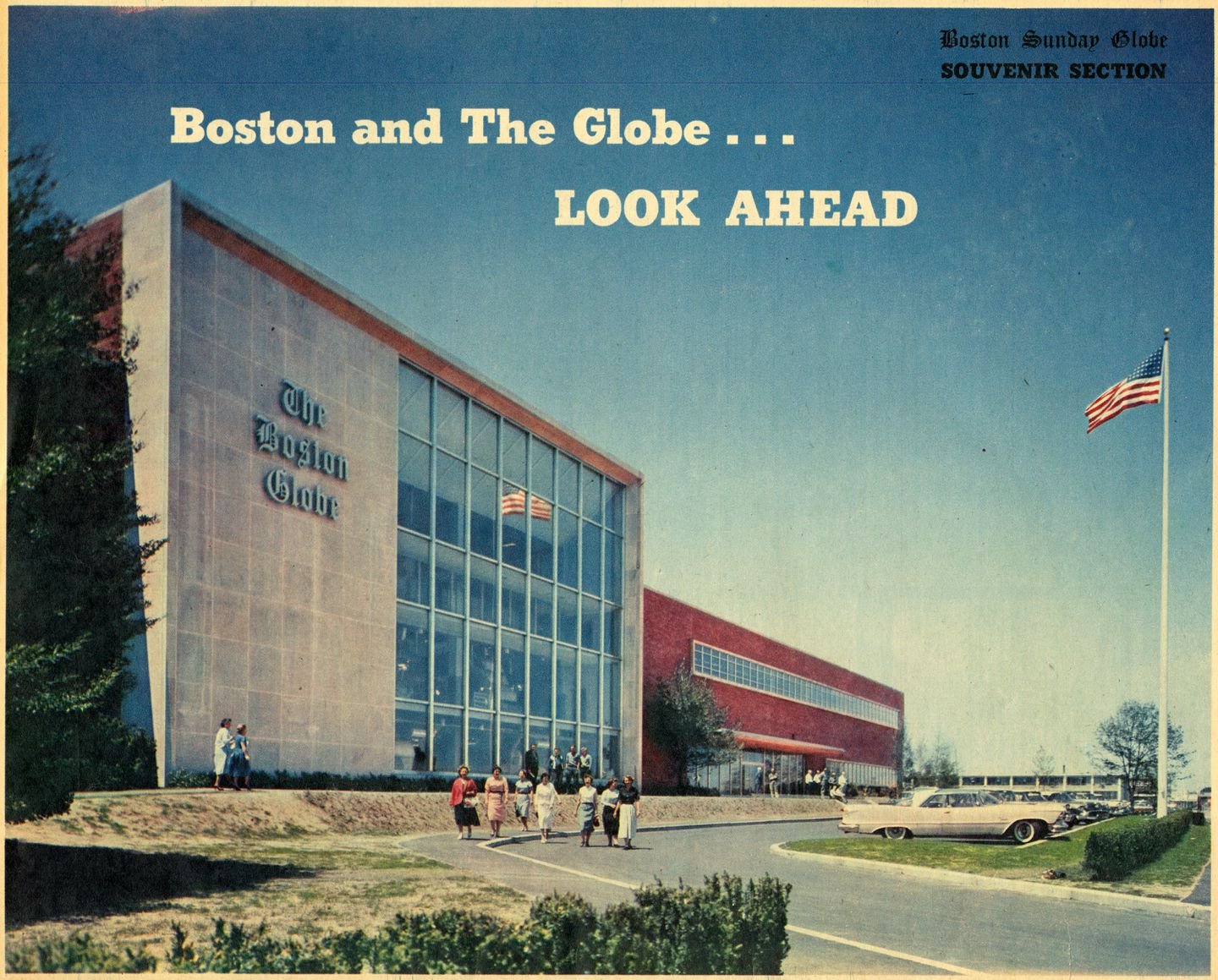

Meanwhile, my reputation had preceded me, and the Globe came calling. By August of ’95, I became an inmate at the massive Dorchester complex that happened to be near exactly nothing. Upon arriving in Boston, I was incredulous that the city’s paper of record was located anywhere but downtown, where the action was. Isolated between the anodyne University of Massachusetts campus and dreadful Interstate 93, we colloquially referred to the Globe as Siberia or likened it to an oil rig. The vertically integrated facility with its immense printing plant was, no doubt, quite a sensation in the modernist era of 1959 when it debuted, a reprieve from the grim confines of old downtown Boston. One fond memory is that of the Morrissey Boulevard lobby, which featured a majestic eighteen-foot tall pictorial map of the six New England states rendered in four tons of white Vermont marble. Created by artist Austin Purves for the Boston Federal Reserve Bank in 1953 (gifted to the Globe in 1978), it’s a celebration of post-war optimism that radiated pride of place.

Despite being only a couple miles south of downtown, the Globe’s geographic isolation had a detrimental psychological effect on the organization. It was said that the adjacent Dorchester neighborhood received attention out of proportion to areas north of the Charles River like Cambridge and Somerville because it was too difficult to traverse the byzantine clogged streets in time to file stories. To outsiders, the Globe’s apparent disregard for certain urban areas fed the perception that the Globe and its advertisers were mainly interested in the region’s wealthy suburbs and shore towns. The impression was that it ceded the inner city to the scrappy, conservative Boston Herald and its opposite, alternative weekly, The Phoenix (sadly defunct). Indeed, leveraging affluent New England households explains why The New York Times acquired the Globe in 1993 for an astonishing $1.1 billion (or nearly $2 billion today, adjusting for inflation). That purchase initiated the Times’ strategy to become a national newspaper. The Globe’s expansive printing capacity and vast distribution network would provide the Times instant access to one of the nation’s best-educated and affluent readerships. No doubt a brilliant plan when hatched, it was soon subverted by the perfect storm known as the internet. Almost overnight, the newspaper industry’s lifeblood went on life-support with Craig’s List cleaving its cash-cow classifieds. With that unforeseen development, the value proposition had been torpedoed, and the Times would later unload the Globe for a mere $70 million in 2013 to Boston Red Sox owner John Henry. The Times pivoted to developing its successful digital brand, the first major media operation to deploy a paywall that defied the widespread belief that consumers were unwilling to pay for web content. By 2017, meanwhile, the Globe’s editorial office had returned to its historical origins on Newspaper Row (currently Exchange Place), Boston’s financial and political beating heart.

• • •

Having achieved what I thought I had wanted, work at the Globe would become a disappointment. As the new guy in a 20-person art department, I was tasked with assignments other designers considered undesirable. Anything other than soft lifestyle content was thought dry, devoid of flourish, and best avoided. Fortunately, I relished the opportunity to redesign the Business Section and take on Focus, the Sunday week-in-review section. That led to assignments with the Globe’s stellar investigative skunkworks team known as Spotlight. Among their credits includes exposing the massive Catholic clergy sexual abuse scandal, taking down Boston’s powerful—and previously untouchable—Cardinal Bernard Law, and others in the church hierarchy implicated around the world.

Though I was long gone before that bombshell, it had been rewarding and meaningful to work on the serial investigation detailing the devastating Malden Mills six-alarm fire in Lawrence, Massachusetts, one of the most horrific blazes in state history. Over 200 firefighters battled 50-foot walls of flame fueled by strong, dry wintry winds that left a wide berth of devastation.

It was a learning experience to witness how a major daily paper functioned. Or didn’t. Someone in a position to know once told me that there was not a single person at the Globe who understood the process from beginning to end. Everyone stayed in their lane, handing off when it came their turn in a daily relay race. Anyone who overstepped was sternly reprimanded. Touch a piece of copy in the past-up department and don’t be surprised to see a t-square coming for your head. I’m not exaggerating. The plodding, tedious pace—especially for a multitasker like me accustomed to involvement in every aspect of the magazine building and selling process—was a difficult adjustment to make. Shut out from participation in photography was especially nettlesome, as it had been previously at Sports Illustrated and Newsweek. Though I understood the necessity of separating design and photo functions at large and dynamic organizations, it was unsatisfying to be isolated into the limiting role of layout.

I moved up to Page One, which was briefly thrilling because I could observe and collaborate with the editorial A-Team. But it didn’t begin to fill an 8-hour day since it comes together within a short window by early evening for that evening’s press run, to land on doorsteps by dawn. It was a privileged experience, though not especially challenging and left me straining at the leash for more action.

I would have gladly taken on more, though the organizational structure didn’t allow it. As was common in American publishing in those days, the Globe was vastly over-staffed. And with a powerful union safeguarding your job, nearly everyone who walked through the door became a lifer, ensconced in the Velvet Coffin, as it was known. The protection in this union town was so ingrained that anything short of a homicide conviction, it seemed, would not count as cause for dismissal. Even then, perhaps, there remained a good chance the union could muscle its way through just to demonstrate its mettle. Staff designers had accumulated years’ worth of tchotchkes and personal bric-a-brac that made their cubicles resemble a teenager’s bedroom. Those fine folks were going nowhere. As staffer numero 20, my prospects for advancement in the design department were slim to none. Though a job for life held no appeal. Quite the opposite, it was frightening. I craved the variety and risk/reward of magazines and the creative energy that all that crazy cross-pollination generated. The uncertainty of it all made you sharper, more decisive, and more inventive. I missed the adrenaline of parachuting in to take on a project with a whole new set of challenges, acing it, then moving on to the next one.

One year after joining the Globe, I resigned to reinvent a fledgling alternative biweekly paper that I had approached cold. The Improper Bostonian had accepted my proposal to re-imagine what was essentially a messy tabloid and elevate it into the big leagues as a legitimate magazine. I saw an opportunity to make my mark on the city by leveraging the brand’s most critical assets: A bright, ambitious young publisher in Mark Semonian; a seasoned editor-in-chief in Nancy Gaines (whose husband, award-winning journalist Richard Gaines, had led The Boston Phoenix); and a brilliantly clever, original name. All that was needed was repackaging. My strategy was to position it to compete with Boston Magazine, the city’s namesake publication, owned by a carpetbagger from Philadelphia. It was calculated to put the Improper on the map and me on B-mag’s radar. Done and done. By August, one year after leaving the Globe, the city had an exciting new magazine called The Improper Bostonian, and I would become the Art Director of Boston magazine.

2007 redesign debut issue several years after returning to the Improper. It’s complicated. (For more Improper covers, click here for the City tab.)

Like the Globe, Boston magazine focused on affluent suburbanites who frequented the city for cultural, dining, and shopping experiences. However, newly-installed editor-in-chief Craig Unger and his lieutenant, veteran reporter, and Chicago-native John Strahinich were not interested in the typical, inoffensive city magazine pablum. Their passion was for meaty crime stories and power profiles. They wanted exposés on the bigfoots that ran business, politics, and academia and hold them to account. Or, in some cases, to celebrate them.

It was an exciting time, with smartly-conceived and well-executed stories that shattered the city magazine paradigm, winning newfound respect for the brand’s solid reporting and writing. Unger, a Harvard Crimson alum, is possessed of a reputation so impressive that it relegates his accomplishments at Boston magazine to a footnote. Since leaving the magazine, he has published eight books, including House of Bush, House of Saud, featured in Michael Moore’s documentary Fahrenheit 9/11. In 2018 his groundbreaking book House of Trump, House of Putin: The Untold Story of Donald Trump and the Russian Mafia, peeled back the curtain on the ties between the Trump Organization and Russian business associates.

Strahinich also returned to his roots and is currently Executive Editor at the Boston Herald. Together, they made a formidable team that shined a light on the dark underside of the city. More than our irascible, Philly publisher Herb Lipson would have liked. Though they were savvy not to ignore the city mag tropes popular with advertisers. They merely delegated that stuff, successfully navigating an editorial mix that gave the publication standing in league with esteemed regional titles New York magazine and Texas Monthly.

Among Unger’s genius moves were planting his flag on the hill of culinary and oenophile excellence. Upon his appointment as EIC, he immediately recruited renowned food critic Corby Kummer (winner of five James Beard Awards) from New York magazine, laying down a marker perfectly timed to coincide with Boston’s chrysalis moment as a culinary destination. We captured the era of the celebrity chef on its ascent with a constellation of rising stars that included Todd English, Jasper White, Barbara Lynch, Ken Oringer, Chris Schlesinger, Michael Schlow, Lydia Shire, Andy Husbands, and others. Collectively, they changed the perception of Boston as a bland, parochial, culinary backwater nearly overnight. And we owned that space. (Though the Improper was developing its own firepower in food and wine critique, at twice the frequency.)

Boston magazine was among the first publications to explore the dynamic of alternative families five years before same-sex marriage was legalized in Massachusetts, the first U.S. state to extend legal rights and protections to gay couples. Written with empathy and sensitivity by staff writer Gretchen Voss and photographed by the extraordinary photographer (and good friend) Dana Smith.

At the close of my third year, Unger abruptly left over a contract dispute with Lipson. Nominally installed as both Editor and Design Director, I made some changes. My favorite franchise would become the back page. Modeled on Vanity Fair’s celebrity quick-take, we dialed up the snark to puncture our subject’s often well-developed armor. How serious-minded persons respond to off-the-wall questions is quite revealing, we discovered. Without question, the most adroit was then-Senator John Kerry. The dour statesman effortlessly and gamely returned our nutty volleys with grace, humor, and cutting wit, smashing his crusty, proper Brahmin persona to bits.

That was typical of the editorial conceits that made magazines compelling and fun to work on. One devious scheme had us skirting the edge when we embarked on a subterfuge targeted at elective cosmetic surgery, a fast-growing advertising category. Stories of unethical doctors upselling expensive and unnecessary procedures to insecure women were increasingly common. We wanted to parse out whether it was standard practice, urban legend, or just a few unscrupulous docs. Surgeons are well-known to possess god complexes, but cosmetic surgeons are in a league of their own. Lording over vulnerable patients, women mostly, their power of suggestion is enormous. Patients literally place their faith in a doctor to magically improve their self-image and a change of fortune. It’s a complicated dynamic with ample opportunity for exploitation. And the possibility of their work—legitimate or not—going irreversibly sideways is ever-present.

We enlisted an attractive, desirable young female reporter in her early 30s who, by most measures, had nothing wrong that needed fixing. She had scored consultations with five prominent physicians seeking advice on improving something or other, probably her nose since that’s where it usually starts. I don’t recall the exact outcome, but the results confirmed our worst suspicions—and a cover story was born. We augmented the package with photos taken during an actual procedure. Great stuff. It’s what we were built for.

On reflection, the number of categories we covered and executed to a high standard was impressive. In an era where the general interest magazine was considered a failed, outdated concept, that’s exactly what we were. Every issue had an editorial mix covering disparate topics including crime, politics, education, health care, transportation, real estate, technology, finance, and business. Plus entertainment, restaurant, book, and theater reviews, shopping, arts, high- and lowbrow culture, music, fashion, relationships, interior design, retail, travel, sports, celebrity . . . and maybe the best bagel shop. Virtually everything.

Typical of the city magazine genre, we adhered to an editorial calendar with theme issues intended to sell advertising packages around Fall Arts in September, Education in October, Holiday Shopping in December, Top Doctors in January, the Power List in May, and so forth. The crescendo was the much-anticipated, soup-to-nuts, jam-packed Best of Boston compilation that landed with a thud each July.

Aside from the obligatory stuff, which some of us embraced, we relished the opportunity to capitalize on news and celebrity misadventure. In my third issue, we opened an annual feature called the Golden Turkey Awards (modeled after Esquire’s consistently outstanding Dubious Achievements) with an arch satire of the latest sex scandal involving the Kennedy clan, catnip for Mr. Unger, who held America’s royal family in the highest contempt. News broke that 39-year-old Michael Kennedy, scion of the late Robert F. Kennedy, had had a three-year affair with the family’s babysitter beginning when the girl was 14. We ran with it, and the resulting lampoonery blew up, landing far beyond Boston to Page Six of the New York Post.

The original image, with a Kennedy stand-in. Our female actor/model played the disgusted babysitter role to perfection. The satire went viral before viral was a thing. Photograph by Frank Veronsky in New York. (Check out the hilarious deck on the layout.)

That was November of ’97. The very next month, on December 31, Michael Kennedy died tragically in a ski accident in Aspen, Colorado, instantly casting that ribald attempt at humor as deplorable. The following year, the Boston Globe fired its two marquis columnists, a mere six weeks apart, for indefensible incidents of plagiarism and fabrication. We drew the obvious parallel to the recent blockbuster film Titanic, with local legends Mike Barnicle and Patrica Smith as Jack and Rose in the ‘flying’ scene on the ship’s bow, oblivious of what was to come. Our crosstown colleagues at the proud Globe were none too pleased that we tooled on their moment of disgrace.

Karmic payback would come in the form of outrage caused by a deeply regrettable coverline for an otherwise outstanding 10,000-word profile on Harvard scholar Henry Louis Gates, Jr., a leading authority on Black history, culture, and racism. (Remember his sit-down for beers with Barack Obama and the Cambridge cop that arrested him for breaking into his own home? Yeah, that guy.) In the piece, Unger, who penned the profile, reports that among his peers, ‘Skip’ Gates caustically and self-deprecatingly refers to himself as the “Head Negro In Charge.” Clearly amused, Unger deploys said quote on the cover—next to Gates’ classy portrait (albeit in quotation marks). All hell broke loose, and Unger would soon be defending himself and the magazine on local news programs against charges of racism by appropriating an archaic word that whites are forbidden to speak. The piling-on was entirely disproportional since the profile was clearly a celebration of the man, not a hit piece by any measure. And, to reiterate, it was a quote. Gates milked it too, feigning offense which served to expand that splendid little scandal into several news cycles. In Gates’s defense, I expect it was a bit embarrassing for a silly insider’s running gag to get played up in a public forum. Though I suspect he, like Unger and owner Lipson, coveted the attention. One outcome for the magazine was the message that it was now a player. Before Unger’s leadership, the most provocative thing expected of Boston Magazine would be a ranking of the city’s best ice creams. The fact that they landed Henry Louis Gates, Jr. in the first place signaled its clout.

Unger had left New York for the job, tapping his Harvard and MIT connections for visionary content by prominent thinkers like Stephen Pinker, Doris Kearns Goodwin, and Lawrence Summers, the latter also the subject of a hefty profile. For all Unger’s access to academia and its alumni, rough-rider second-in-command, Strahinch matched it with robust Boston business and media connections. They formed a dynamic-duo leadership team supported by a stellar, talented crew on par with any national magazine. Several staffers, Sean Flynn, Andrew Goldman, Jay Cheshes, Kelly Alexander, and Benoit Denizet-Lewis, to name a few, went on to national prominence at GQ, Vanity Fair, the Wall Street Journal, Saveur, The New York Times Magazine, and others.

With bosses #1 and #2 concentrating on exposés and profiles, lifestyle content—and fashion in particular—fell to me and my fashion director, Australian-native Gabrielle Derrick de Papp. Coming from our collective experience in New York, we realized that covering fashion had to be done at a high level or not at all. The talent required to pull off serious fashion content exists in relatively few cities globally, and Boston was definitely not a fashion capital. Unless it was still-life product shots, we never considered shooting locally, which seems astonishing now that we had the resources and support to think big. We shot mainly in New York, LA, and Miami Beach because that’s where the talent was. Hair, makeup, models, and photographers; they just didn’t exist in Boston at that level. Which is not a knock on Boston. The city was simply not on the map as a content producer for that highly specialized industry, so it could not cultivate those talents. And we wanted to be indistinguishable from national magazines in everything we did. To deliver an exemplary product for our consummate, sophisticated readers, we had to go big or go home, as the cliché goes. We chose the former.

It was a special time and place. From what I’ve seen and experienced since then, local talent has emerged who can play in that sandbox.

I plan to post more images of work from that era as it becomes available. Thanks for reading.

—J. Heroun

I wouldn’t change a thing. Display copy (heads, decks, captions), art, and design still feels sharp and contemporary more than 20 years on. If I designed a magazine that looked like this now, it would feel in-step with our current era.