My Neighbor, the Wheelie King

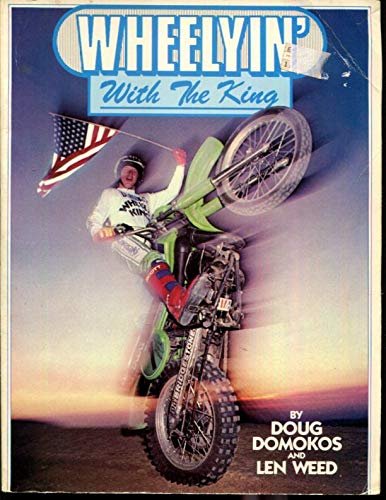

The Wheelie King in action.

It was a Sunday morning like most others, with the shrill wail of the high-strung Yamaha piercing the air, its rider in the endless pursuit of the perfect, show-stopping wheelie. The Domokos household next door was tucked back from Warren Road at the apex of the small suburban circle dotted with post-war ranch-style homes of varying pedigree. Their expansive lawn provided Doug a wide berth to practice and refine the daredevil skills for which he became renowned.

Our bland, isolated, 1950s housing development branched off Michigan highway M-40, about five miles north of Niles. A small city, Niles supported two high schools and a significant, robust downtown retail sector that sloped down to the turbulent St. Joseph River that flowed through town on up to Lake Michigan. Situated 10 miles north of South Bend, Indiana and the University of Notre Dame, Niles claimed Ring Lardner, John and Horace Dodge, rock star Tommy James, and the retailer Montgomery Ward as its scions. A little industrial powerhouse, owing to its proximity along a major waterway and midway between Detroit and Chicago by rail, Niles punched above its weight. In the Nineteen Twenties and ’30s, well-off denizens of the Four Flags City boarded the early evening train to Chicago for theater and dinner, returning the same night. That Victorian-era train station is featured in the films Continental Divide with John Belushi and Blair Brown, Midnight Run with Robert De Niro and Charles Grodin, and Only the Lonely, a John Hughes film starring John Candy, Maureen O’Hara, and Ally Sheedy.

Warren Road and Effie Lane, two halves of the circle that formed our rural Eden, were carved from pristine farmland. One of the earliest so-called subdivisions built throughout the United States for homecoming soldiers after 1945, it lay just beyond Dead Man’s Curve. That treacherous patch of two-lane asphalt preyed upon unsuspecting speeders and impaired drivers who entered the twisties a little too hot. In the halcyon days before drinking and driving were frowned upon, the S-curve sent cars careening down a 20-foot ravine to a watery end in the tranquil trout pond below. (That stretch has since been straightened, and the highway was renamed M-51.)

A half-mile north, Zeke’s Gulf filling station marked the entrance to Warren Road. On relentlessly scorching summer days, I’d seek refuge in the cool shade of the station’s garage after a tedious afternoon of mowing our quarter-acre of parched, weedy lawn infested with hysterical giant grasshoppers. My reward was an ice-cold, ten-cent Nehi Grape pop from the big metal cooler stocked with RC Cola, root beer, and Squirt.

Summers could be oppressive. Weeks of blistering heat and humidity, invariably followed by terrifying greenish-black skies foretelling tornado warnings, sent everyone fleeing to their basement sanctuaries. The winters were worse. Brutalized by frigid, stiff winds that gathered strength across the vast plains of the midwest, turbocharged by the lake effect of the inland sea a mere twenty miles west, we endured an unrelenting snowy misery for much of the year. On those early wintry mornings, we’d muddle through snowdrifts, woefully underdressed, out to the corner where Zeke’s met the highway. Anxiously awaiting the shelter of the lumbering school bus, dreading the long, tedious ride, time stood still as cold gusts lashed our red faces and chilled our bones.

Our little suburb sat at the edge of a large corn field that abutted woodlands cleaved by dirt paths remaining from abandoned railroad tracks. Across the highway, the Dowagiac Creek meandered through thickets, making its way to the churning St. Joseph River further downstream. A couple miles closer to town lay a larger, tonier subdivision with sexy street names derived from cars, like Impala, Invicta, Catalina, and Thunderbird Drive, where Donna Herman lived. I often wondered what it was like to live there among those better off than us, for whom money was always scarce. Most days, I was reminded of that unpleasant reality as I rode past the upscale enclave along the highway on that dorky red Schwinn, dutifully tending my paper route in the poor Black neighborhoods near the train depot on the southern edge of town.

The Domokoses’ house was grander than most others in the circle. Their property extended to our modest house on the west side of their property, backed by the massive corn field and adjacent wilderness, where the popular dune buggy excursions took place. The low-slung, single-story ranch style home with the flagstone entrance seemed opulent to my naive eyes. Its long, gently-curved driveway led to the gaping yaw of a multi-car garage that served as a de facto automotive workshop. At most any time, sparks from arc-welders would illuminate the early evening while the clanging of metal against metal rang out. The family patriarch was a kind, soft-spoken man who always made us kids feel welcome to observe whatever projects were underway. Doug, the oldest child, shared his father’s gentle outward nature while a competitive fire quietly simmered within. Liz, his younger tomboy sister, was cool, up for anything, and fun to hang with. I don’t remember much about the family’s mother, other than she was racked with depression, reclusive and rarely seen.

Bloody Sunday

One day I spied the family Olds station wagon towing a beaten, dead Volkswagen Beetle on a flatbed. This was around 1968 or ’69, at the height of the dune buggy craze that repurposed expired Bugs into groovy fiberglass-bodied kits that evoked the carefree California surf lifestyle popularized on television shows like “Here Come the Monkees”. The Veedub was shorn of its dilapidated body and renewed as a bright, shiny yellow bug-eyed dune jumper. Its exposed rear-mounted engine was modified with chromed bling and fancy, burbling tailpipes to complete the rebel beachcomber vibe. Us neighborhood kids were treated to joy rides, giddily bouncing around the backwood trails. The Domokoses were enshrined as the coolest family in the community.

Shortly after Doug’s morning dirt bike calisthenics that fateful Easter Sunday morning, a dune buggy outing formed that included my opposite next-door neighbor, Mike Gessinger. Mike, the eldest of three siblings, was a popular, handsome student, burgeoning tennis star, and well-rounded athlete like his younger brother Chris. Good-natured, quick-witted kids, the boys excelled at every sport and personified the all-American spirit of the era. At around 10am, their panicked mother and others sprinted across our backyard toward the Domokos homestead. The commotion drew me outside, where I witnessed the blue Olds inexplicably speeding through the corn field and disappearing into the outback. Word spread that there had been an accident with the dune buggy. A short time later, they reappeared with Mike lying dead in the back of the wagon. The buggy, which had not been outfitted with roll bars or seat belts, had flipped on a dirt mogul, landing upside down with Mike under it, crushing his skull. To my everlasting horror, the image of Mike’s limp, bloody body in the back of the wagon awaiting the ambulance is indelible.

The yellow dune buggy was retired following the incident. Remarkably, the Gessingers never pressed charges or held the Domokos family responsible. That evening, a bright full moon hovered ominously over the eastern sky, illuminating the swampy, eerie edge of the circle where no houses had been built. Spooked, I looped the moonlit circle endlessly on my bike, trying to process what had happened, stunned by the brutality, saddened for Mike’s family. At my tender age I had had some experience with death, though it involved elderly folks, inevitable and peaceful. Now, a kid about my age whom I had admired had perished suddenly, improbably, violently, in the most awful chance encounter. It seemed an unbearable tragedy, more so given Mike’s many gifts. A boundlessly bright future snuffed out moments after experiencing joyful abandon.

World Renown

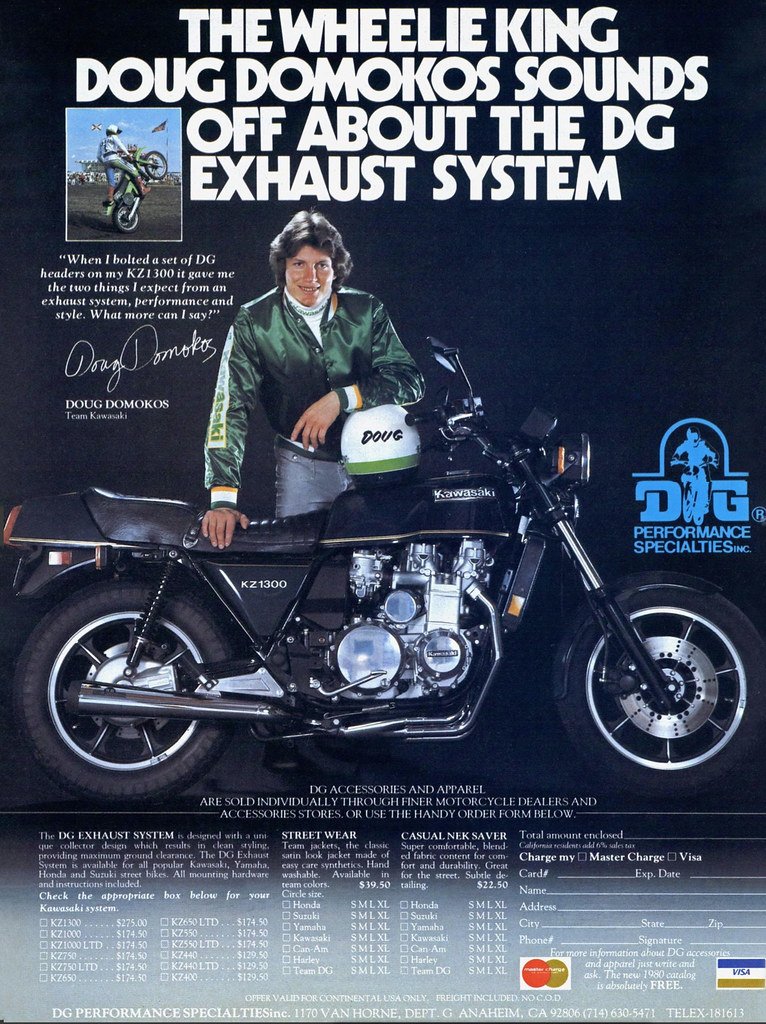

A couple years later we moved to the opulent westside of Niles, far from Warren Road. Doug Domokos, two years my senior, receded from memory, leaving high school as I entered my sophomore year. I later learned that the endless days of wheelie practice had paid off handsomely for him. He had become an international sensation, performing before thousands in arenas worldwide. He performed for the Emperor of Japan and once circled the Empire State Building roof deck five times, apparently edging towards becoming a successor to the bombastic, fearless Evil Knievel. Partnering with Kawasaki, he helped engineer motorcycles specifically optimized for his stunts. Among his most astonishing feats was a mind-bending 145-mile wheelie at Talledega Speedway. It landed him in the Guinness Book of World Records and secured his place in the American Motorcyclist Hall of Fame. It didn’t surprise me to discover that this kind, lion-hearted man was known to have performed shows for several charities and organizations. Doug also penned a book called Wheelyin’ with the King, where he shares his secrets for stunt riding, along with a bit of his backstory.

The undisputed wheelie king, Doug Domokos, met an untimely death, though not involving his beloved bikes. On November 26, 2000, while piloting an ultralight aircraft in California, Doug perished along with his flight instructor Keith Lamb. According to Wikipedia, he left behind his fiancé and their son, Nikolas. I wish them the best. Doug was a good man. Intelligent, quietly self-assured, brave, and sensational. It was evident from the beginning that he was bound for greatness. How random that I knew him when. —J. Heroun

Doug’s book is available on Amazon.